Trust The Process: Nike Free

Natural Motion

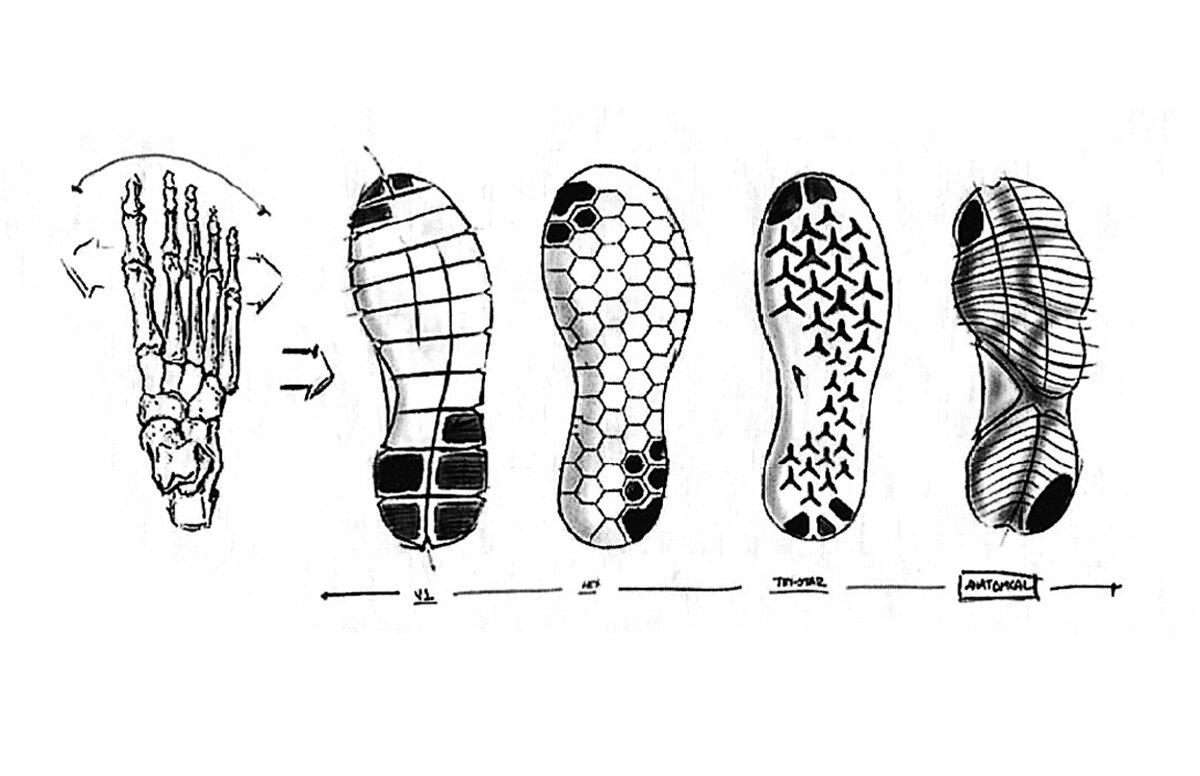

In 2001 a group of Nike designers (that included Tobie Hatfield) observed Stanford University runners training barefoot on the grass of the university’s golf course. This sparked an idea to explore the athletic benefits of a more natural approach to running. Partnering with researchers from Nike’s Sport Research Lab (NSRL) they were able to measure pressure mapping and motion capture to analyse the biomechanics of running barefoot on grass. The findings from the lab showcased that the foot had a more natural strike and flexibility, which over time increased the runner’s balance and strength. This established a clear focus for the designers: break up the bottom of the shoe in order to better mimic the articulation of the natural foot. Through their exploration Hatfield thought of the construction of ice cube trays and how they segment solid blocks of ice, making it easy to bend the tray. Inspired by this the team designed a new kinetic last (above) assembled from multiple sections and connected with a piece of flexible material. The resulting segmented form better simulated the organic motion of the foot and became a driving symbol behind the birth of the Nike Free series.

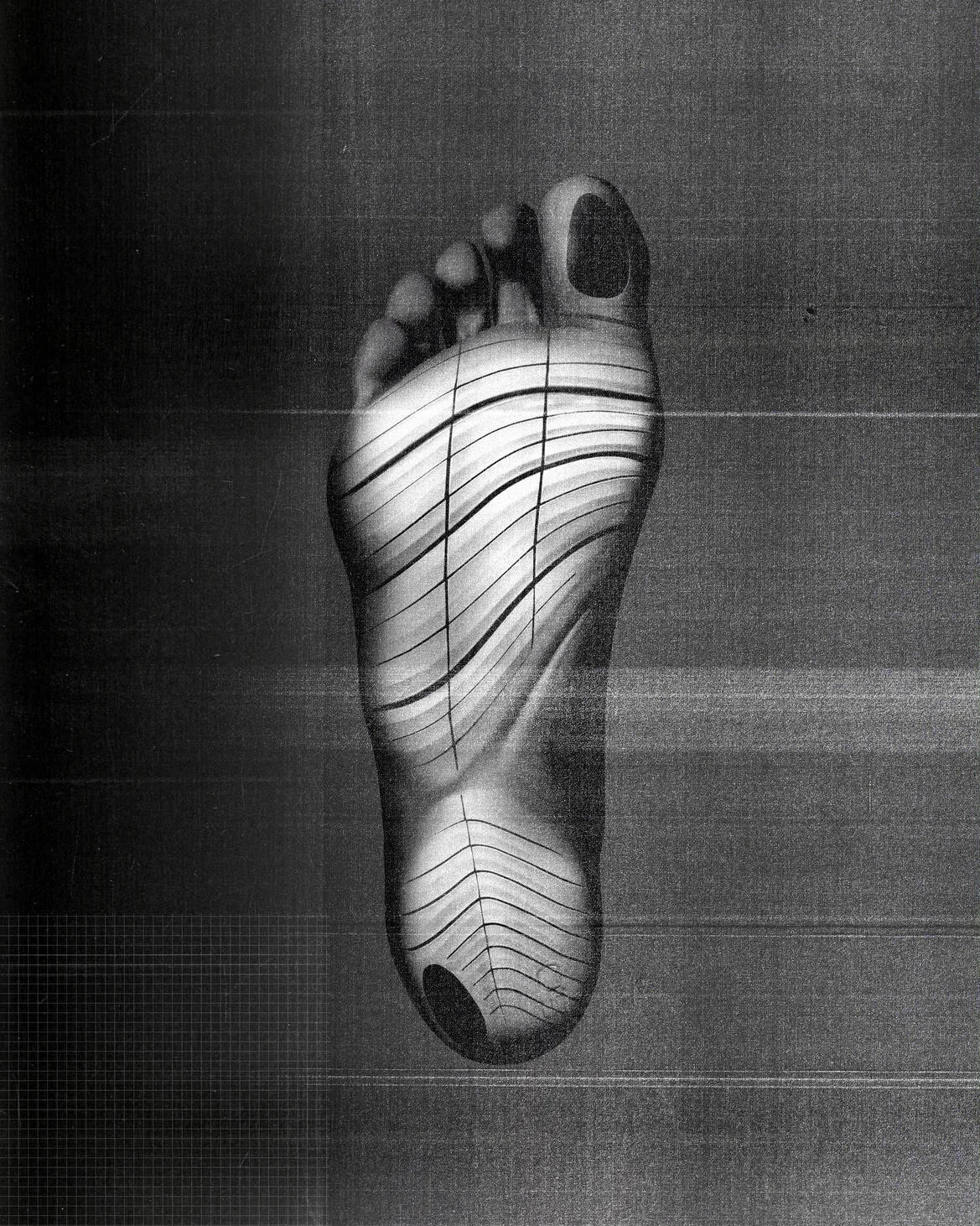

Through a pursuit to replicate the barefoot as closely as possible, the team created a prototype which replicated a second skin like structure. This featured silicon pads affixed to a thin, lightweight mesh which looked more like a ballet flat than running shoe. This mode of thought continued to inform how the outsole could be broken up by wrapping the foot with minimal material.

“People ask me why we never made a Presto 2. I always tell them we did — it’s called the Nike Free.”

Tobie Hatfield

In 2014 new research from NSRL showed that as the foot loads, it expands and contracts on two planes: lengthwise (from heel to toe) and widthwise (across the arch). Until then, Free’s siping only handled the heel-to-toe flexion. Wondering if there was a smarter way to design cuts, designers started experimenting with auxetics, which are structures that, when stretched, expand in two directions.

Designers played around with various auxetic patterns before landing on the tri-star shape, which resembled the hexagon outsole pattern Free had already established, because they could tune it, to a degree. The splaying, auxetic midsole mimics how the body and foot react to force. It absorbs shock while accounting for the dual-plane expansion in foot size (approximately one size in length and two sizes in width) that occurs throughout an athlete’s foot strike. The multi-directional outsole flexibility closely mimics this changing shape, whether an athlete is moving linearly in running or multi-directionally in training. The resulting flexibility puts the foot, rather than the shoe, in control.

The continued advancements in the brand’s running category has been propelled by findings from the Nike Sports Research Lab. They play a key role in the study of athletes, spending hours observing and diagnosing all of the requirements needed to continually improve performance. By collating this information and leveraging science and technology, Nike is able to improve on product which already seemed to be at it’s peak. Often this may even be a development of existing designs without new technology or materials. Simply rethinking the way a product is utilised and how it interacts with the body is an innovation tool that few other brand’s do better.