Trust the Process: Mecha

Walking Machines: Bipedal Power

Depictions of the future in media present a wide array of possibilities for how techwear design may progress, as we have found through previous looks at video game designs, the optimal testing ground for the success can be found in some surprising yet exciting places. Robotics design has been an experimental venture in technological advancements, yet its thorough exploration throughout media has generated mass appeal and for us proven to be a valuable tool in considering the potential that footwear design has. Perhaps more so than any genre within robot depictions to be a source of inspiration for us are “walking machines”, more commonly referred to as mecha.

Created in the fallout of the second world war and popularised in Japan, mecha were first specifically seen in the works of Osama Tezuka and Mitsuteru Yokoyama in the 1950s, with Tezuka’s Mighty Atom - known widely as Astro Boy and Yokoyama’s Tetsujin28-go - also known as Gigantor. The walking machines in these manga were designed to be simplistic and chunky with a strong silhouette, forgoing any technical detail despite their robotic components. Being designed as reactionary to the war, their immense range of superpowers made them more appealing to a younger audience initially, until the arrival of Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam (1979), which helped shift the mecha focus from the “Super Robot” genre into the “Real Robot” genre. This transition traded the superpowers of the super robot for more conventional futuristic weaponry and abilities, presenting more limitations based in real technological convention.

With the rise in popularity of the dystopian cyberpunk genre, another shift into more streamlined yet technically complex cybernetics became more of a focus thanks to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and Shirow Masamune’s Ghost in the Shell (1995). Here, the human body effectively became a walking machine through becoming cybernetic itself or using more focused armatures and exoskeletons. As this progression of mecha media portrayals occured, so too did the advancements of real world mecha, as seen by the mechanical creations of Boston Dynamics and Korea Future Technology. We have delved through this expansive timeline and examined the mecha that may have the potential of turning techwear into mechwear.

From Xenogenesis (1978) to The Terminator (1984) the works of James Cameron typically feature a relationship between humans and technology, with technological apparatuses being used for a variety of purposes in depictions of the future world. In Aliens (1986), set in the 2100s, the military team that aids Ellen Ripley implores a variety of technology including the iconic Caterpillar p-5000 Powered Work Loader. Designed as a mech suit assisting construction, Ripley’s use of the suit heavily challenged gender norms while also demonstrating the progression of technology in this time, eventually using it to battle the Alien Queen in the film’s finale. This steel-reinforced exoskeleton is gyro-stabilised to keep balanced with the hydraulic powered feet allowing the entire apparatus to remain steady when moving and carrying loads. When used on rough terrain, the Power Loader will send feedback cues to the user to help keep their footing, but due to the immense downward pressure if used on soft ground the whole mech could potentially bury itself.

In his 2009 film, Avatar, mech exoskeletons are featured as a way of highlighting the disturbance technology has on nature, here the Amplified Mobility Platform (AMP) suit is used to face the Na’vi in battle on Pandora. Featuring a cockpit chest for the driver, they appear similar in design to Armoured Personnel Unit (APU) in The Matrix series, though more streamlined. The inclusion of pedal-like feet give the AMP a necessary follow-through from heel to toe, challenging the rigidness often seen in mechs, increasing the speed and mobility of the suit. Considering its size the suit is made of lightweight materials, yet the lower legs and feet were reinforced to protect against mines as well as support any high jumps.

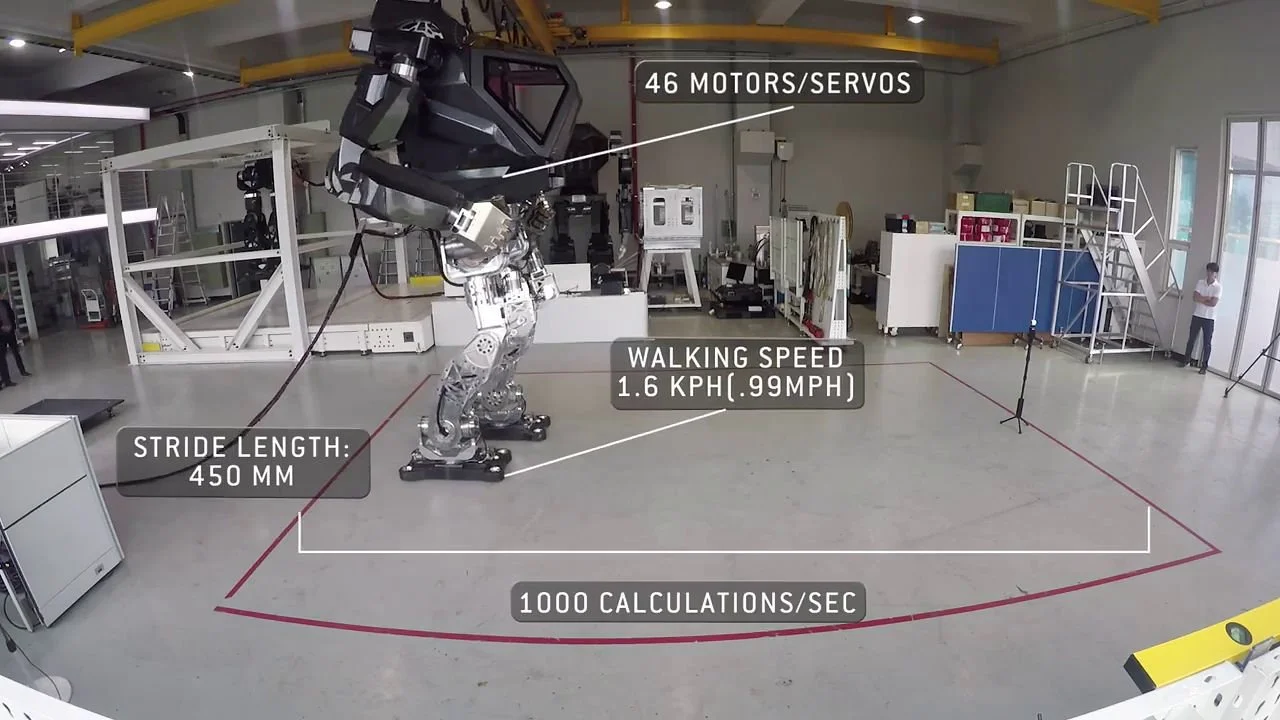

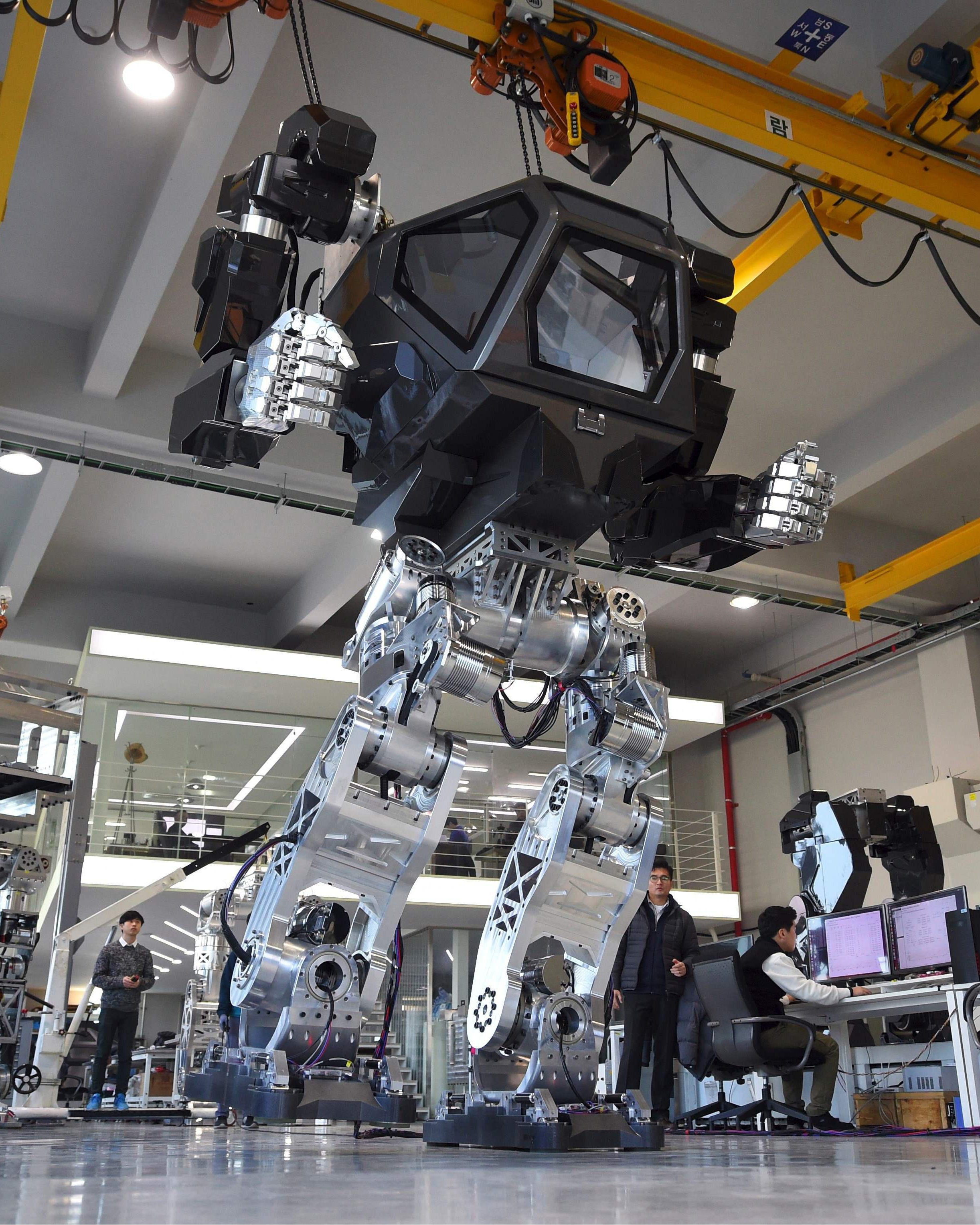

When compared to the Power Loader, the AMP offers a more fully realised depiction of mech design, with the exoskeleton being more versatile and free in its movement, which is not surprising given how by the 2000s technology had vastly improved since the eighties. In The Matrix series, the feet of the APU feature several toe-like additions, producing a greater surface area for the mech to stand on to support the more material-heavy design, yet decreasing the speed and nimbleness of the upward-spade feet of the AMP. Interestingly, these designs have already impacted the development of real robotics. The METHOD-1 mech by Korea Future Technology created a bipedal robot to house a human pilot, designed by Vitaly Bulgarov. Bulgarov is no stranger to machinery design, having worked on Terminator: Genisys, which was produced by Cameron. Featuring a similar overall design to the AMP, METHOD-1 may prove that our notions of the future are already closer to present day than we realise.

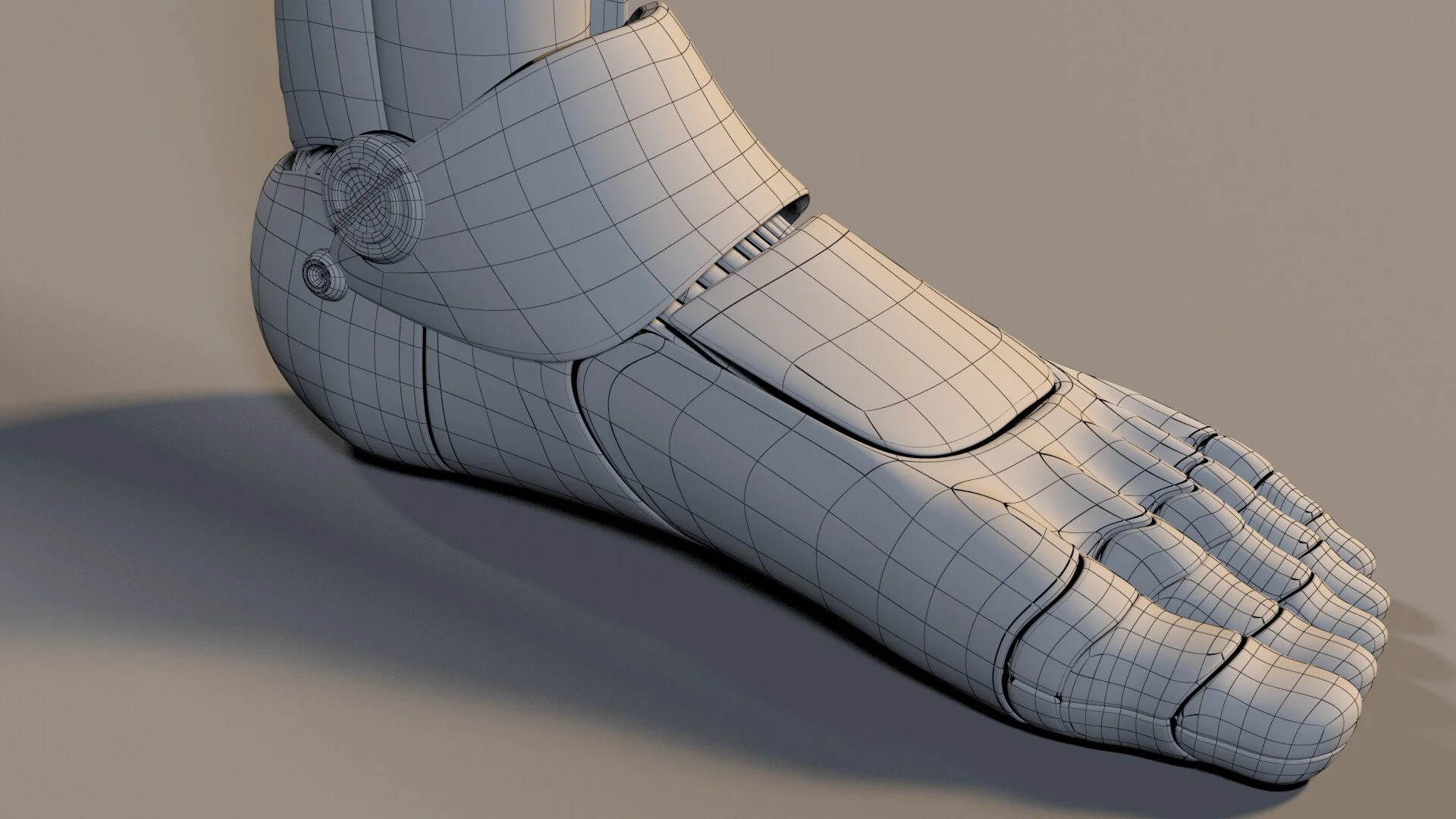

Depictions of technology and mechanical advancements in cyberpunk media often feature greater symbiosis between the human and robotic self, furthering on from the limitations of the “real robot” into cyborg/android territory. Both Major Motoko Kusanagi from Ghost in the Shell and Alita from Battle Angel Alita are major examples of the true advancement of robotics. In many ways descendants of the super robot, Astro Boy, the more realistic and humanoid designs of these characters is how they demonstrate to us the progression in how we understand tech. These “walking machines” are designed to be human-like but enhanced in every way - Alita’s feet for instance allow for plasma generation, boosting her speed to supersonic levels and allowing for a supercharged kick.

Raiden, of Metal Gear Solid, eventually possessed his own cybernetic body, complete with enhanced feet designed to include a unique tooling design along the extended heel, which emulates a high heel with the perk of being able to grip and use his sword, allowing for greater range of attacks when spinning in combat. Though technically a cyborg, his body, like Alita’s or The Major’s, is capable of being upgraded and redesigned in the same way designers may improve technological design yet it's their use of these bodies that simulates the growth and progression of an athlete. It certainly raises questions about body modifications and the autonomy of technological bodies versus the use of techwear.

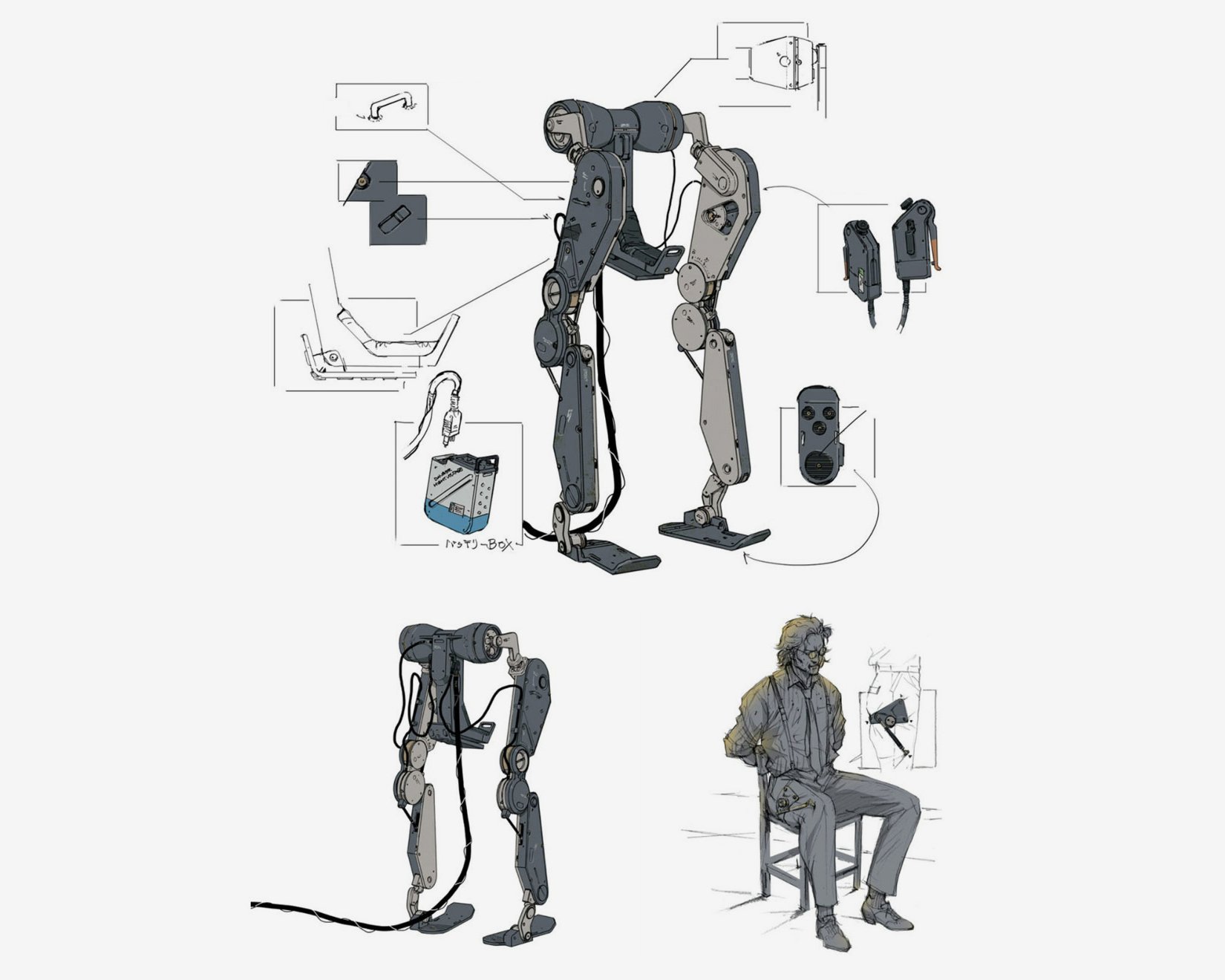

Neill Blomkamp’s films seem like an amalgamation of the robotics within Ghost in the Shell and Cameron’s work, with Elysium (2013) looking at augmentation through mechanical enhancement and CHAPPiE (2015) directly comparing mech-like walking machines and humanoid-like machines. The exoskeletal attachments that Max DeCosta receives in Elysium act as enhancers to his movement, being surgically bolted into his joints and connected via neural implant to facilitate his movements. In many senses he wears the tech as much as it is a part of him. The armoured metal plates across his body provide him the necessary protection in his harsh journey, with the extensions to his legs and feet improving his speed capabilities and making an ordinary man into effectively a super soldier capable of going toe-to-toe with the robotic police seen in the film. Reminiscent of the real Human Universal Load Carrier (HULC), there is clear real life applications of similar taking place, bridging the gap between the fictional and reality.

Blomkamp’s short feature, ADAM (2017), showcased an endoskeleton almost entirely the opposite to DeCosta’s, being able to fit inside the human body and enhancing from within. The design takes the human form further, with Leo Haslam’s designs containing multiple limbs but importantly the ability for the legs to become double hinged, appearing more animalistic and less human. On a practical level this ideology of design could increase speed and reflexes if used in real technology, and perhaps offers a better relationship between body and tech than the design from Elysium.

In CHAPPiE, the titular robot is inspired by real robotics manufacturer designs, appearing intentionally realistic when compared to other sentient robot characters seen onscreen. He is built to be slender yet his block-like limbs evoke the design of earlier mecha, albeit with a closely detailed appearance bearing the bolts and clear manufacturing detail. With well articulated fingers and toes, with the latter creating a tabby-like design for his feet - not dissimilar to those possessed by the Prophet in ADAM - enhanced by pistons placed in his heels, these design features are more appropriate for his size and human-quality when compared with the AMPs of Avatar.

It’s interesting to note that throughout most depictions of walking machines, the machines themselves utilise the human bipedal silhouette, either through accommodating the person controlling the mech or creating empathy for the audience. In reality the design of robotics often incorporates a variety of mobility functions based on the primary design requirements of the machine. Boston Dynamics, founded in 1992, are known especially for their robots BigDog, Spot and Atlas. Presenting the closest reality to autonomous mecha, particularly in the form of Atlas, Boston Dynamics have progressed both the technology and engineering of contemporary robotics but also have consistently challenged the dystopian image their robots have received. In multiple videos, such as this, where Atlas dances and even performs parkour you can see the reality of bipediple mecha is not far from the concepts of Blomkamp’s CHAPPiE, where its flat, tread soled feet enable it to recreate complex human actions to perfection.

The sheer breadth of walking machines through history was only just touched on here and considering how techwear is constantly evolving, the industry can certainly take note of the progression of robotics. Footwear tech can be seen as an augmentation or extension of our bodies, responsive not only to developing technological performance but the individual experience of the wearer. This mindset may be the key to paving the way for footwear technology to allow humans to become walking machines of our own.